Pick of the week image:

Failure is the best way to learn, you can and should try to optimize it

Thu Sep 08

Written by: Chris Pohlman

Pick of the week image:

Two weeks ago I spoke about PCG (procedural content generation) and mentioned it was a staple of a video game genre known as rogue-likes. That same genre is often known for another game mechanic, perma-death. That is to say that every time your character dies they are gone forever and you have to start over from the beginning. If your goal is to reach the end of the game this obviously provides a pretty major hurdle. In order to beat the game you have to do it it in one shot without making any major mistakes.

That’s impossible, or that sounds like it isn’t any fun at all, or maybe oh those must be games for only really hardcore gamers, you might be thinking. But if you can get past the one inevitable truth behind playing a rogue-like, that you will fail and die a lot, then I think anyone can play them and have a great time. More importantly I think anyone can learn some valuable lessons from them. I’ll go over the 2 I find to be most important here.

One of the biggest challenges when it comes to learning from failure is getting good feedback about when and how you went wrong. In life in general this can often be tricky since you might not get an opportunity for feedback until long after you did the thing you are getting feedback on. Video game makers know this and for the rogue-like genre where failure is a core game mechanic getting you that feedback as early and often as possible is key to a good experience. Often times a full successful run could take as little as 30 minutes and an unsuccessful run much less. If we can apply this to things we are attempting to learn or improve at in day to day life you can get much better faster. This means taking whatever you are trying to do or learn or improve at and figuring out what the minimum time version of that thing is. The minimum viable product or MVP. Don’t get stuck in the trap of thinking you have to do something huge and complicated just because the thing you are trying to learn can be huge and complicated.

In some cases that is easier than others of course. Learning to cook for example is an easy thing to fail quickly at, You could go out a buy 30 eggs and attempt to cook each one over-easy and since they cook quickly you could get dramatically better in just an afternoon. Assuming you pause to reflect between each egg. That’s the key here, reflection. Reflection is also something you can do no matter what the skill is that you are working at. So next time you are trying to learn something or improve a skill, Do it as often as you can, fail a lot, and reflect on why you think you failed in between each attempt.

I’d be willing to bet a lot of people naturally had their mind go to the idea of an experiment when thinking about reflecting in lesson 1. In my experience though its much harder to do in practice when it comes to larger decisions especially. Maybe you think about starting your own business, or want to jump into a new industry. Well try making it into an experiment. If for instance you want to become a software engineer, think about what a full-time software engineer might do everyday. Then try doing as many of those things as you can and see how they feel. You probably can’t create your own meetings, but you can totally code everyday. You can even find open-source projects to try to contribute to, and get to experience what working on a larger existing code-base is like. And again reflection is key here, try things out, frame them in your mind as an experiment so you can go all-in without feeling permanently attached to the decision, and reflect on the outcomes.

This week my girlfriend and I welcomed two new members into our family, Azula and Bumi

Azula is the tortoise shell looking girl and Bumi is the tabby boy. Our older cats are still learning to love them but they are starting to come around.

This week I learned about the @property decorator in python. It allows you to write functions in your classes that work as getters and setters without needing to write separately names functions for each role which is less “pythonic”. They are called decorators since they go above your functions and “decorate” them changing the functionality they typically have.

class Rectangle(Measurment):

def __init__(self, length, width):

self.length = length

self.width = width

@property

def length(self):

return self._length

@length.setter

def side(self, length):

self._length = length

@property

def width(self):

return self._width

@width.setter

def width(self, width):

self._width = width

def perimeter(self):

return (self.length + self.width) * 2

def area(self):

return self.length * self.width

def __str__(self):

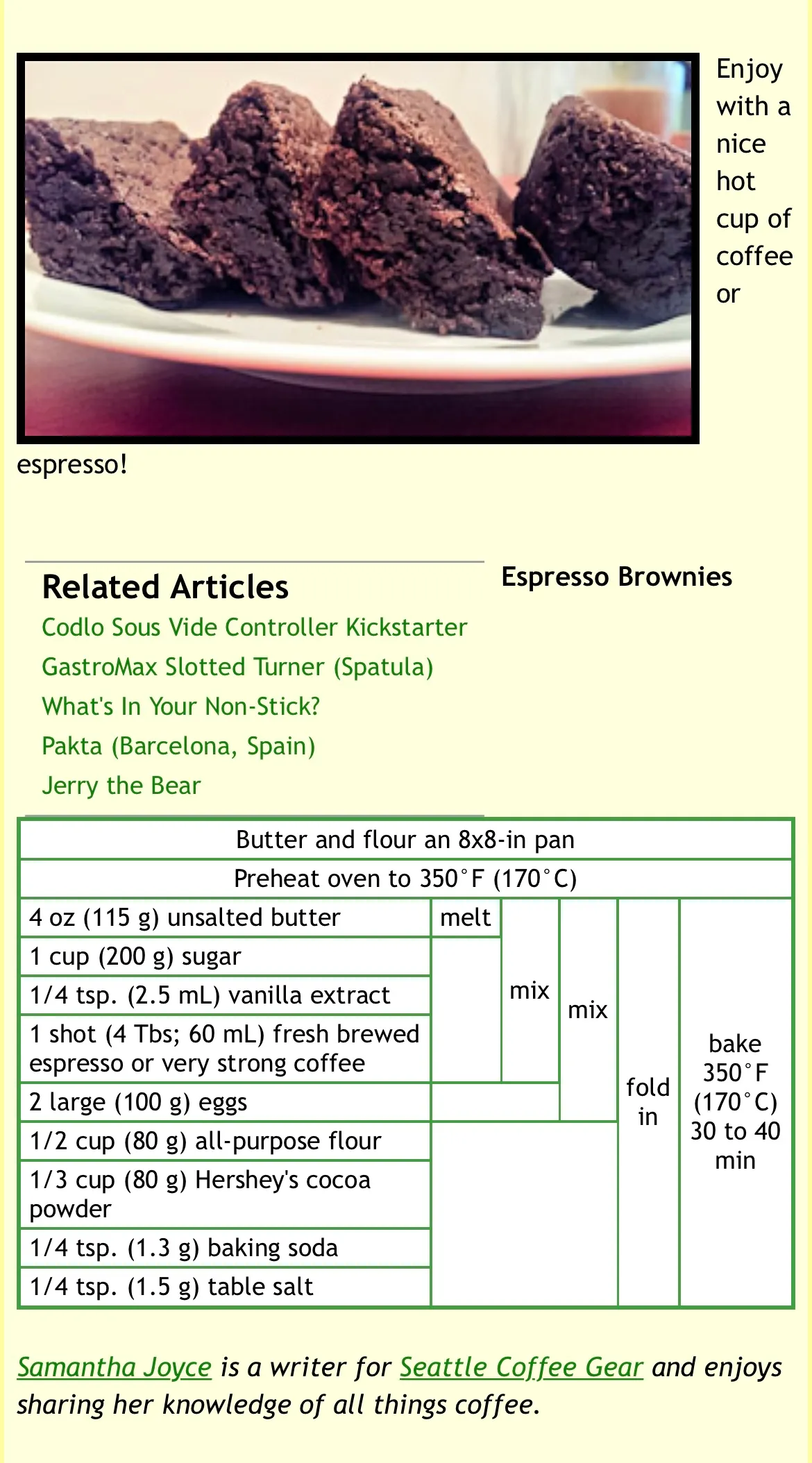

return f'Rectangle with length {self._length} and width {self._width}'In the light of talking about experiments and learning new skills, this weeks pick is cooking for engineers. Cooking for engineers is a blog that takes a unique approach to recipe writing and formatting that can help unlock a better understanding of how to approach recipe following. Below is a screenshot of what their recipe format looks like.